The Transcendent Legacy of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: Master of Qawwali

The Transcendent Legacy of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan: Master of Qawwali

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, widely revered as “Shahenshah-e-Qawwali” (the King of Kings of Qawwali), transformed the devotional Sufi musical tradition of qawwali from a relatively niche religious practice into a globally celebrated art form. His extraordinary vocal range, improvisational genius, and spiritual depth captivated audiences across more than 40 countries during his prolific yet tragically short career. Khan’s remarkable ability to perform intense, spiritually charged concerts lasting up to 10 hours, combined with his innovative approach to traditional qawwali, earned him recognition as one of the greatest singers of all time by Rolling Stone magazine and NPR. His legacy continues to influence contemporary qawwali performers, Bollywood music, and artists across various genres worldwide, cementing his status as not just a musical icon but a cultural bridge between East and West.

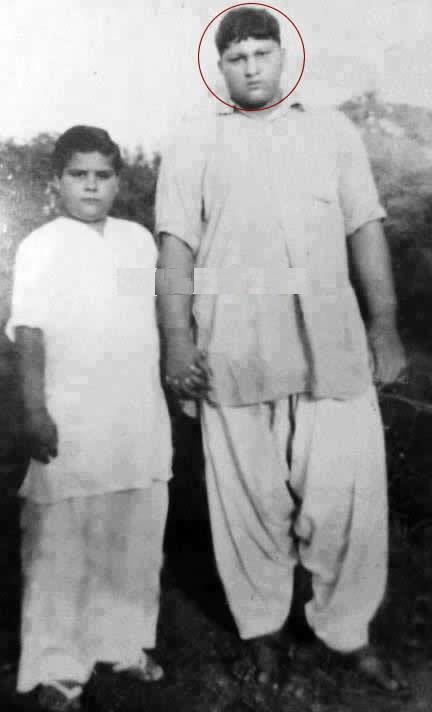

nusrat fateh ali khan qawwal

Born into a Punjabi Muslim family in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad), Pakistan in 1948, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan was the inheritor of an extraordinary musical legacy spanning six centuries. He was the fifth child and first son of Fateh Ali Khan, himself an accomplished musicologist, vocalist, instrumentalist, and qawwal. The tradition of qawwali in Khan’s family had been passed down through successive generations for almost 600 years, creating an unbroken chain of musical knowledge and spiritual expression. This profound heritage provided the foundation upon which Khan would eventually build his revolutionary approach to qawwali.

Interestingly, Khan’s father initially opposed his son following in the family’s musical footsteps, preferring that he pursue a more prestigious career as a doctor or engineer due to the relatively low social status afforded to qawwali artists at that time. Despite this parental resistance, Khan demonstrated such natural aptitude and passionate interest in qawwali that his father eventually relented, allowing the young Nusrat to begin his musical training. This tension between tradition and innovation would become a recurring theme throughout Khan’s career as he simultaneously honored ancestral practices while dramatically expanding the boundaries of qawwali.

Khan’s early musical education was immersive and comprehensive, occurring within the tradition-bound context of his family’s qawwali party. Like many musical prodigies throughout history, Khan’s initial role was humble – he joined his father’s ensemble as a tabla player while continuing to develop his vocal abilities under careful tutelage. This period of apprenticeship allowed him to absorb the intricate rhythmic patterns, melodic structures, and devotional essence of traditional qawwali from the inside out, developing the technical foundation that would later enable his groundbreaking innovations.

The trajectory of Khan’s career changed dramatically in 1964 following the death of his father. At just 16 years old, the young musician assumed leadership of the family qawwali party alongside his uncle Mubarak Ali Khan. This transition marked the beginning of Khan’s evolution from student to master, though his full artistic emergence would require several more years of development and experience. After his uncle’s death in 1971, the ensemble was renamed “Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Mujahid Mubarak Ali Khan & Party,” before eventually becoming known simply as “Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan & Party,” reflecting his growing prominence and distinctive artistic vision.

One of Khan’s earliest public performances as leader of the family qawwali group occurred in March 1965 at a studio recording broadcast as part of Radio Pakistan’s annual music festival, Jashn-e-Baharan. This performance proved pivotal in establishing his reputation, drawing praise from legendary classical musicians including Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Ustad Umid Ali Khan, Roshan Ara Begum, and Ustad Amanat Ali Khan. Such recognition from established masters of Pakistani classical music helped legitimize Khan’s approach to qawwali and expand its audience beyond traditional devotional contexts.

Among Khan’s first major hits in Pakistan was the Punjabi qawwali “Ni Main Jana Jogi De Naal,” which he composed and first performed live in 1971, with a studio version subsequently recorded in 1973. The lyrics to this breakthrough composition were written by Bulleh Shah, a 17th century Sufi poet whose mystical verses would feature prominently throughout Khan’s repertoire. Another significant early success was the qawaali “Haq Ali Ali,” which showcased Khan’s restrained yet powerful use of sargam improvisations – a technique of vocal soloing using the Indian solfege syllables that would later become one of his most distinctive stylistic signatures.

Khan’s musical approach represented both a continuation of tradition and a bold reimagining of qawwali’s possibilities. While he remained firmly rooted in his family’s style, which dated back to the beginnings of qawwali, he also contributed a substantial body of original compositions and perfected certain musical techniques that set him apart from his predecessors and contemporaries. Most notably, Khan developed a unique hallmark of reciting sargam (solfege) at extraordinary speed over multiple simultaneous and complex rhythmic patterns – a feat of vocal dexterity that astonished both casual listeners and trained musicians.

KIng Qawwal: Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

The expansiveness of Khan’s repertoire was another distinguishing characteristic of his artistry. He mastered not only the Khusrau songs in Hindi and Farsi from the original classical qawwali tradition but also the rich body of work created by Punjabi mystic poets over centuries. His heritage as a Punjabi allowed him to interpret these texts with particular authenticity and emotional resonance, connecting with audiences across religious and cultural divides. In a groundbreaking development that reflected his inclusive spiritual vision, Khan became the first qawwal to sing selections from the Guru Granth Sahib (Sikh Holy Scriptures) in the qawwali format, raising renewed awareness of the mystical verses found within diverse religious traditions.

Khan’s performances were characterized by an extraordinary intensity and stamina that seemed to transcend normal human limitations. He regularly delivered concerts lasting up to 10 hours, maintaining exceptional vocal quality and emotional engagement throughout these marathon sessions. This remarkable endurance reflected not only his technical mastery but also the deeply spiritual nature of his musical practice – qawwali for Khan was not merely entertainment but a vehicle for transcendence, a means of “reducing the distance between the creator and the created,” as he himself described it.

The last decade of the 20th century witnessed what music scholars have described as an “amazing musical phenomenon” as Khan transported qawwali – traditionally the mystic music of Sufi initiates performed in sacred enclaves – to secular audiences worldwide with unprecedented success. This transformation represented not just a personal triumph but a cultural watershed, as a musical form previously accessible primarily to religious specialists suddenly found resonance with listeners across continents and traditions.

Khan’s international career accelerated dramatically after signing with Oriental Star Agencies in Birmingham, England in the early 1980s. This partnership enabled him to release recordings and perform concerts throughout Europe, India, Japan, Pakistan, and the United States, exposing entirely new audiences to the spiritual power of qawwali. His touring schedule became increasingly intense throughout the 1990s, as if, some observers noted, “he realized time was running out”. During this period, Khan performed in more than 40 countries, building a fan base that stretched from Trinidad to Korea and Norway to New Zealand.

Remarkably, Khan achieved this global recognition despite several factors that might have limited his appeal to Western audiences. Qawwali is entirely text-driven, relying on a deep understanding of multiple layers of meaning drawn from the mystic verses of South Asian and Persian poets. The fact that Khan could profoundly move listeners who understood none of the languages he sang in testifies to the universal emotional quality of his performances and the transcendent spiritual energy he channeled through his music.

Although the search results don’t provide a comprehensive list of Khan’s most famous compositions, they do mention some of his breakthrough works. “Ni Main Jana Jogi De Naal” stands as one of his earliest significant compositions, first performed in 1971 and recorded in 1973. This Punjabi qawwali featured lyrics by the 17th-century Sufi poet Bulleh Shah, demonstrating Khan’s deep connection to the mystical poetic tradition. Another early hit, “Haq Ali Ali,” showcased his innovative approach to sargam improvisations, which would become a signature element of his style.

Khan’s repertoire was remarkably diverse, encompassing classical qawwali standards, his own original compositions, and interpretations of devotional poetry from multiple religious traditions. He performed Khusrau songs in Hindi and Farsi from the original classical qawwali repertoire, works by Punjabi mystic poets, and, in a groundbreaking development, selections from the Sikh Holy Scriptures. This breadth reflected not only his consummate musicianship but also his inclusive spiritual vision that transcended sectarian boundaries.

As Khan’s international profile rose, he engaged in numerous collaborations with Western artists, becoming a prominent figure in the emerging “world music” scene. Many musicians across genres sought to work with the qawwali master, resulting in joint ventures featuring his distinctive vocal style in diverse musical contexts. While some purists may have questioned these cross-cultural experiments, they significantly expanded global awareness of qawwali and created new hybrid forms that continue to evolve today.

Despite his commercial success and international celebrity, Khan remained committed to the spiritual essence of qawwali throughout his career. Even at the height of his fame, he continued to perform authentic qawwali for little or no compensation in the humble settings that represented the tradition’s roots. This dedication to maintaining qawwali’s spiritual integrity while simultaneously expanding its reach exemplifies the balance between tradition and innovation that characterized Khan’s artistic journey.

Khan’s impact extended far beyond the specific tradition of qawwali, profoundly influencing musicians across genres and cultural contexts. Many prominent artists have cited him as a major source of inspiration, including Jeff Buckley, who famously described Khan as “my Elvis” and occasionally performed segments of Khan’s compositions during his own concerts. Other musicians who acknowledged Khan’s influence include Peter Gabriel, A.R. Rahman, Sheila Chandra, Alim Qasimov, Eddie Vedder, and Joan Osborne, demonstrating the breadth of his artistic legacy.

In the realm of electronic music, producers have continued to find inspiration in Khan’s recordings years after his death. In 2007, electronic music producer Gaudi released “Dub Qawwali,” an album featuring entirely new compositions built around Khan’s vocals from archival recordings. This project achieved significant commercial success, reaching number 2 on the iTunes US Chart and becoming the top-selling release in Amazon’s Electronic Music section, indicating the enduring appeal of Khan’s voice even in radically different musical contexts.

Perhaps most significantly, Khan’s music had a transformative impact on Bollywood soundtracks and contemporary South Asian popular music. He inspired numerous Indian musicians working in the Bollywood industry from the late 1980s onward, including prominent figures like A.R. Rahman and lyricist Javed Akhtar, both of whom collaborated with Khan directly. His influence was so pervasive that many hit Bollywood songs openly borrowed or plagiarized elements of his compositions, sometimes prompting good-humored responses from Khan himself, who reportedly once jokingly presented “Best Copy” awards to composers Viju Shah and Anu Malik.

Khan’s untimely death on August 16, 1997, at the age of 48, cut short an extraordinary career that had fundamentally transformed the global perception of qawwali. Despite his relatively brief life, his cultural impact has continued to grow in the decades since his passing. His nephew, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, has carried forward the family’s musical legacy, becoming a celebrated qawwal and playback singer in his own right. Additionally, numerous tribute albums, documentaries, and scholarly analyses have examined various aspects of Khan’s artistry, cementing his historical importance.

The full measure of Khan’s influence on qawwali as a genre cannot be overstated. Before his international breakthrough, qawwali occupied a relatively low position in the hierarchy of South Asian musical traditions, considered inferior to classical forms like khayal and dhrupad. Khan’s extraordinary success dramatically elevated the status of qawwali, bringing unprecedented recognition to this devotional art form. Moreover, many listeners first encountered Indian classical raags (melodic structures) through Khan’s qawwali performances, ironically reversing the traditional prestige hierarchy within South Asian music.

Beyond his musical innovations, Khan’s career represented a powerful demonstration of art’s ability to transcend cultural, linguistic, and religious boundaries. His performances created spaces where listeners from diverse backgrounds could share in a profound spiritual experience, regardless of their familiarity with the specific theological contexts of the music. This universal quality was recognized in 2015 when Google celebrated Khan’s 67th birthday with a doodle on its homepage in six countries, describing him as the person “who opened the world’s ears to the rich, hypnotic sounds of the Sufis”

Conclusion

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s extraordinary journey from a traditional qawwali family in Pakistan to international musical icon represents one of the most remarkable cultural phenomena of the late 20th century. His revolutionary approach to qawwali—preserving its spiritual essence while dramatically expanding its technical vocabulary and audience—transformed a regionally specific devotional practice into a globally recognized art form. Through his hundreds of recordings, extensive touring, and numerous collaborations, Khan introduced millions of listeners to the transcendent emotional power of qawwali.

Despite his immense commercial success and artistic experimentation, Khan never lost sight of qawwali’s core purpose as a vehicle for spiritual elevation. His ability to balance innovation with tradition, global appeal with cultural authenticity, and technical virtuosity with emotional directness makes him not merely the greatest qawwali performer ever recorded but one of the most significant musical figures of modern times. More than two decades after his passing, his voice continues to resonate across cultural boundaries, offering listeners worldwide a glimpse of the divine through the medium of devotional song.

Ramadan 2025: A Month of Spiritual Cleansing & Compassion

Ramadan 2025: A Month of Spiritual Cleansing & Compassion